On the Marking of Books

Reading A Book for All It’s Worth

I am firmly of the opinion that if you read a book without “marking it up” then you are not really reading it for all its worth. I offer as a concession that there are those books, typically fictional in nature, which taking the time to annotate them might somehow seem to harm the romance of the story. Sometimes one should read for absolutely nothing but the pleasure of it and lose themselves in the world the author has made.

Even so, I have reached a point in my own reading and annotating of books that I feel a very genuine pleasure in engaging books in this way. Even books in which it is a pleasure to lose myself I find that I want to go back to them and mark them up. I, in fact, love them even more once I have done so. Why? Because I see so much more than ever before when I slow down enough to engage them in this way.

Marking and annotating your books makes them thoroughly your own. You’ll investigate them, shake out their every detail, become intrigued by the smallest of those details, and you’ll find you have so many points of curiosity that you want to explore. When you mark and annotate a book you become more conscious of their connections to other books you have read. Subtle allusions to other great works are all over the place and, I dare say, sometimes the author makes them without even realizing it (especially when they are allusions to Scripture or Shakespeare).

Once you develop a consistent system for marking and annotating books, and give it a bit of practice, it becomes second nature. I am personally unsatisfied at this point if I read a book without marking it. It’s like listening to a movie blindfolded; you still get the gist but you really miss out on a lot. But having a consistent method is really the key. Allow me to offer you my own approach.

Get yourself a set of erasable pens with the following colors:

Black: For general underlining and marginal notations.

Red: For vocabulary, key terminology, and references to other literary works.

Blue: For characters/historical persons.

Green: For dates and events.

Purple: For places (cities, states, countries, particular businesses, schools, etc.)

You can, of course, pick your own colors but consistency is key.

Here are a few other useful rules:

Only mark a person, place, word, or event the first time it appears in a given text. In other words, if you are reading a biography of Abraham Lincoln or encountering Ebenezer Scrooge in A Christmas Carol you will only mark their name the first time they appear in the text. This also follows with any other person/character mentioned in the book and the same goes for the other color coded categories. This will allow you to easily find when a person or character first makes their entrance in the story as you flip through the book later.

When you use your general underlining pen (Black in my case) have a reason. If you don’t have a reason, don’t use it. If you do have a reason, note it. Write in the margin what your thought was as to why you underlined. This can be many things. Perhaps you write simply, “Ha!” Because it amused you. Maybe you write down a Bible reference it brought to your mind or a quote from another literary work that touches the same topic. Maybe you note “This was beautifully said” or “What a foolish thing to do.” You can also just note in the margin what the topic is being discussed. Regardless, it stood out to you to underline…why? Write it in the margins.

Have some things you are looking for on purpose. Two categories I try to be on the look out for are Virtues & Vices and Great Ideas.

As to the first I focus primarily on the 7 main virtues and their corresponding vices (Cardinal and Theological). The Cardinal Virtues are Prudence, Temperance, Fortitude, and Justice. The Theological Virtues are Faith, Hope, and Love. I am always looking for great examples of these in literature and history and trying to take note of them. Equally valuable are the corresponding vices in the form of excess or deprivation.

As to the second there are the “Great Ideas” which are essentially concepts which are found in abundance throughout literature, religion, and philosophy. These Great Ideas are of universal value because they are timelessly interesting and equally so to all people in all places. Arguably all of the above virtues are also Great Ideas but I find it useful to give them their own category. Other examples of Great Ideas would be things like “Light versus Darkness,” the concept of “home” or “Coming of age” or “appearance versus reality.” There are many more. Mortimer Adler is always a great place to start thinking about the Great Ideas.

Ask questions! Pretend you are in conversation with the author and/or the characters. What questions come to mind? Write them in the margins or get a notebook and write them down noting the chapter and page they correspond to. It’s helpful to see that there are basically three major categories for the kinds of questions you can ask anyone (or any book).

Grammar Questions: By which I simply mean informational questions. What is it? When was it? Who did it? Any question which can be directly answered by the text is a grammar question. The answers are simply the content of text and should be readily available. Ex. “Who shot Abraham Lincoln?” Answer: “John Wilkes Booth.” I don’t typically write these in the margins for myself but I might write them down to ask students to check their comprehension. The colored highlighting system is to help draw attention to the grammar/information of the text (People, places, dates/events, terms).

Logic Questions: These are questions of interpretation or internal comparison/contrast. They ask “What?” “why?” or “how?” Such as “What does Aristotle mean by happiness?” or “Why is Jill Pole so afraid of Aslan?” or “How can Tom Bombadil handle the ring without it affecting him?” You can also ask questions of consistency “Can statement X said in Chapter 2 be true and also statement Y said here in chapter 4?”

Rhetoric Questions: These are questions of evaluation and external comparison/contrast. “Should the council have sent the ring to Mordor or should they have tried to hide it?” Again, “Are Dante’s depictions of Hell consistent with Jesus’ own teachings on the subject?” Sometimes these pluck a topic from the text to discuss in the abstract, “Plato doesn’t seem to think Justice means simply paying back whatever you owe when it is asked for. How are we to define Justice? What is our standard?”

I truly believe that if you adopt a system like this it will forever alter the way you read a book and it will be for the good. You will see things you’ve never seen before. Take down one of your old favorites from the shelf and try it! You will also be able to relate the information/story back to others with greater memory and precision. You’ll be able to quickly glance at your marginal notes and the subject matter will flood right back into your mind after having not looked at the book in quite some time. Once you start down this path you will ask yourself… “Did I really even read books before I started doing this?”

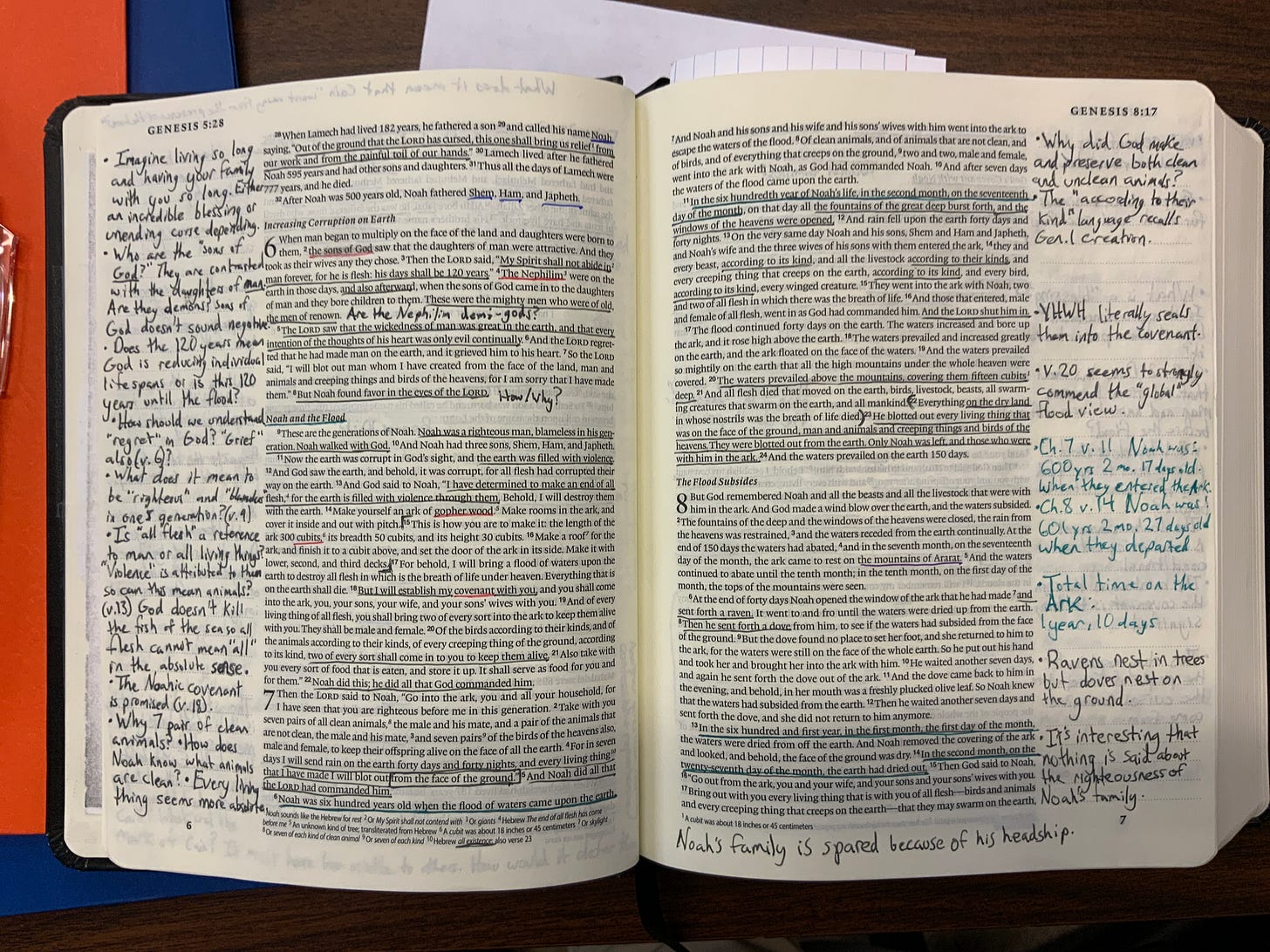

Exempli gratia:

I too cannot read a book without a pen. In fact I won’t move to reading any digital version of a book until someone creates a system that allows me to annotate as effortlessly as I can with paper and pen.

That said I also love buying used books that have been annotated. It’s like having a conversation with the author and another “student”.

Thank you for this! I am starting a Great Books Masters program at the end of the month. I am a homeschool mom of 4 who hasn’t been a student since I graduated from college in 2002! This gives me such a good framework as I start my studies.