The Greek and the Roman peoples, languages, and cultures form two of the three primary pillars of Western Civilization. Their myths, legends, heroes, politics, philosophy, art, storytelling, and architecture continue to have an enduring impact on the world today. As Americans, as with any other Western nation, it is not too extreme to say, “To know the Greeks and the Romans better is to know ourselves better.” Our form of government, many of our cultural customs, and the kind of stories we love to hear and tell, are largely a product of their influence.

If you wanted to focus on myth you might look to Ovid or Hesiod, if you wanted to focus on Philosophy you might look to Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero, and if you wanted to look to epic stories of legend you might look to Homer, Aeschylus, or Virgil. If, however, you want to learn about the great men who shaped Greece and Rome, you should look to Plutarch. Not exclusively, of course, for there are many great historians like Herodotus who give us insight into some of the great men of these cultures. Nevertheless, Plutarch is different because he intentionally focused on giving the world biographical sketches of some of the most pivotal figures in Greek and Roman history. Other writers introduced great men as they came incidentally into their wider histories concerning nations, peoples, and wars. Plutarch, on the other hand, did not write a history of a people per se, rather, he wrote about the lives and deeds of individual men of renown.

Biography is possibly the most potent form of storytelling for the purpose of virtue education because it is about real people and their deeds. The person reading a biography sees virtue and vice in action, in real people and in real places, throughout history, and realizes that such actions can be done again (for good or ill). This is clearly a major part of the purpose of Plutarch’s Lives. He sees the successes and failures of these notable men as examples to learn from. Some men’s actions should be emulated and others avoided and biography helps us to see the difference.

Plutarch tells us of his own intentions in writing his Lives, stating,

It must be borne in mind that my design is not to write histories, but lives. And the most glorious exploits do not always furnish us with the clearest discoveries of virtue or vice in men; sometimes a matter of less moment, an expression or a jest, informs us better of their characters and inclinations, than the most famous sieges, the greatest armaments, or the bloodiest battles whatsoever. Therefore, as portrait-painters are more exact in the lines and features of the face, in which the character is seen, than in the other parts of the body, so I must be allowed to give my more particular attention to the marks and indications of the souls of men, and while I endeavour by these to portray their lives, may be free to leave more weighty matters and great battles to be treated of by others.1

In saying that it was not his “design” to “write histories” Plutarch is clarifying that he is not simply trying to be a chronicler of times and nations but that he intended to highlight particular aspects of the lives of men from which his readers could benefit. He would show us that which provided "the clearest discoveries of virtue or vice in men”.

Histories help us see how and why entire nations rise and fall. Lives (biographies) help us see what makes individual men rise and fall. A healthy nation is only healthy if its individual citizens are collectively virtuous. Plutarch’s Lives gives us much fodder for considering virtue and vice and what makes a person “great.” For greatness can mean many things. A person can be great, that is to say deeply influential and powerful, without being good. But the best of men will be both.

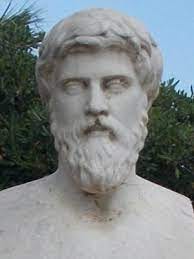

Plutarch himself was a Greek who lived from c.46AD -c.119AD, making him a contemporary of some of the New Testament authors and figures. He was a Stoic philosopher and prolific writer. Beyond his Lives of Noble Greeks and Romans we have more than seventy of his essays, speeches, and some of his letters. His letter known as Contentment is a classic piece of Stoic philosophy and serves as a great introduction to reading Stoic literature. Plutarch’s writing style is always engaging, interesting, and often quite amusing.

For the Christian reader we are able to examine the lives of these great men, not only with the categories of virtue which Plutarch had in mind (Justice, Temperance, Fortitude, and Prudence) but also in light of the Christian virtues (Faith, Hope, Love) and the author of virtue/righteousness himself, Jesus Christ. We can greatly benefit from these sketches of the lives of famous men and we can improve upon their examples of virtue by grace while avoiding their folly by the same divine gift.

Study Guides on selections from Plutarch’s Lives

Plutarch, The Lives of Noble Grecians and Romans, in Great Books of the Western World vol. 13. (Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1990), 540-541.

Are you recommending a particular edition/translation?