This post is part of a series on The Ecumenical Creeds of Christendom. If you would like to go back to the beginning of this series you may do so by clicking HERE.

The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, more commonly referred to as simply “The Nicene Creed,” is the preferred creed of the Eastern Orthodox Churches. Although these churches also affirm The Apostles’ Creed without reservation, the Nicene Creed tends to take precedence in their tradition and they have historically used it for baptismal vows in the same manner in which the Western Churches (Roman Catholics and Protestants) have tended to use The Apostles’ Creed. The reason for Eastern churches’ preference for The Nicnee Creed is fairly straightforward, it was developed among the Eastern churches with little involvement from any of the Western churches or bishops.

When considering the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed it is important to understand that they developed for many similar reasons, but with one important difference. The purpose behind the development of both creeds is similar in that they are obviously meant to confess, positively, what we believe as Christians. Further, the overall function and usage in the Christian church is basically the same for both creeds. Everything which has been said about the usefulness of The Apostles’ Creed in the previous lesson could just as easily be said about The Nicene Creed. The two creeds are, however, different in the purpose of their development concerning one point, namely, the Apostles’ Creed was purely proactive whereas the Nicene Creed was reactive.

In the years leading up to the Council of Nicaea a presbyter in the church of Alexandria, by the name of Arius, had been popularizing the teaching that the Word of God (that is to say, Jesus, the Son of God) is not equal with the Father and is, indeed, of a different substance than the Father. In other words, Arius taught that the Son is like God, being of a similar substance (ὁμοιούσιος) to the Father, but not being of the same substance (ὁμοoύσιος). Arius held the Son of God to be both before and above all other creatures and superior to them in all ways, but still not co-extensive, co-eternal, and of the same substance as God the Father. The Father and the Son are, according to Arius, two different beings and not one and the same in being.

This teaching of Arius caused quite a stir (rightfully so) as it departed from the orthodox teaching of Scripture that Jesus (the Son) is truly God eternal, come in the flesh. Bishop Alexander, from Alexandria, ardently combatted Arius’ teaching. He defended the biblical doctrine that the Son is in every way God just as the Father and the Spirit are God. He argued that the Father, Son, and Spirit are all of the same substance (ὁμοoύσιος). In Greek these words are only different by one letter, the iota, but that one letter difference makes all the difference in this hugely important theological debate.

As a result of Arius’ teaching, and Alexander’s attempts to counteract it, there became a growing disunity in the church Alexandria and beyond and even some civil unrest. Constantine the Great, who had recently won sole authority over the Roman Empire after a period of its being divided among four rulers (which was known as “the tetrarchy”), was eager to have peace in his empire. He had, himself, declared allegiance to Christ (the fascinating story of his conversion is told in good detail by Eusebius in his Church History) and so he now had an interest in the matter both as a ruler and as a professing Christian. As a result, Constnatine ordered the church to convene a council to hear both sides of the matter. This council convened in the city of Nicaea in 325 A.D. and was attended by 318 bishops of the church and many other presbyters, deacons, and interested believers.

Arius was given fair hearing. Afterwards Alexander responded by valiantly propounding before the council the Scriptural teaching that Jesus is, in fact, God in the flesh, truly human and truly divine. After some days of hearing both sides of the debate from the representatives of each position the council voted. Of the 318 bishops who had assembled at Nicaea 298 sided with Alexander that the Scriptures teach that Jesus is truly God in the flesh, of the same substance as the Father. Of the dissenters some advocated for a more moderate position but were willing to sign off on the final decisions of the council. Arius and his most ardent followers, however, refused to recant or repent of their error and were excommunicated. Arius, as a result, was divested of his role as a presbyter in the church and barred from taking the Eucharist (i.e. Lord’s Supper / Communion) within faithful churches.1

The earliest form of the Nicene Creed was a product of this council in its affirmations of the true deity of the Son and the Spirit alongside the Father. The Nicene Creed, as you will see, shares quite a bit of common ground with The Apostles’ Creed and was, doubtless, written with an awareness of some early form of that Creed. Most of the differences between the two creeds are merely that of additions. Those additions were intentionally designed to combat the heresy of Arianism. In this way, the Nicene creed is reactive to the situation that arose and which called for a response. The Nicene Creed, it should be noted, did not invent any new doctrines, rather, it clarified and affirmed the biblical teachings concerning the being of God and the persons in the godhead. The vast majority of the council affirmed this truth because it is what the Bible actually teaches and it is what the church had already been teaching for the past almost 300 years.

The Nicene Creed received two notable updates over the years after the first publication. The first and most substantial (pardon the pun) was that which was made in 381 A.D. at the Second Ecumenical Council which was convened by Theodosius in Constantinople. This later council was convened to combat yet another false teaching concerning the godhead. A group known simply as the Macedonians (or, less simply, as the Pneumatomachians) were denying the true deity of the Holy Spirit just as Arius had denied the true deity of the Son some years earlier. This council, which was convened with 150 bishops (all from eastern churches), affirmed the true divinity of the Spirit (as the earlier Nicene Creed intended) and strengthened the language of the Nicene Creed to more clearly express this truth.

The last notable alteration to the Nicene Creed was introduced in 589 A.D. at the third Council of Toledo, in Spain (though not fully affirmed and standardized in the West until the late 9th century). The addition that was suggested, though small in verbage, was tremendous in its impact upon the relations between the Eastern and Western churches. The alteration in question is that which has come to be known as the “Filioque” clause. Filioque is Latin for “from the Son” and in this context it addresses the question of the procession of the Holy Spirit. Here I quote, again, the work of Philip Schaff:

The Latin or Western form differs from the Greek by the little word Filioque, which, next to the authority of the Pope, is the chief source of the greatest schism in Christendom. The Greek Church, adhering to the original text, and emphasizing the monarchia of the Father as the only root and cause of the Deity, teaches the single procession (ἐκπόρευσις) of the Spirit from the Father alone, which is supposed to be an eternal inner-trinitarian process (like the eternal generation of the Son), and not to be confounded with the temporal mission (πέμψις) of the Holy Spirit by the Father and the Son. The Latin Church, in the interest of the co-equality of the Son with the Father, and taking the procession (processio) in a wider sense, taught since Augustine the double procession of the Spirit from the Father and the Son, and, without consulting the East, put it into the Creed.2

The debate between the Eastern and Western churches over the Filioque clause (as well as the Western church’s commitment to the supremacy of the Bishop of Rome) only mounted over the centuries until in 1054 A.D. the Great Schism of the Church was complete and the Eastern and Western churches no longer met together in any ecumenical councils. The Filioque clause has mostly been accepted among Protestant churches without comment seeing as the Reformation movement began in the West.

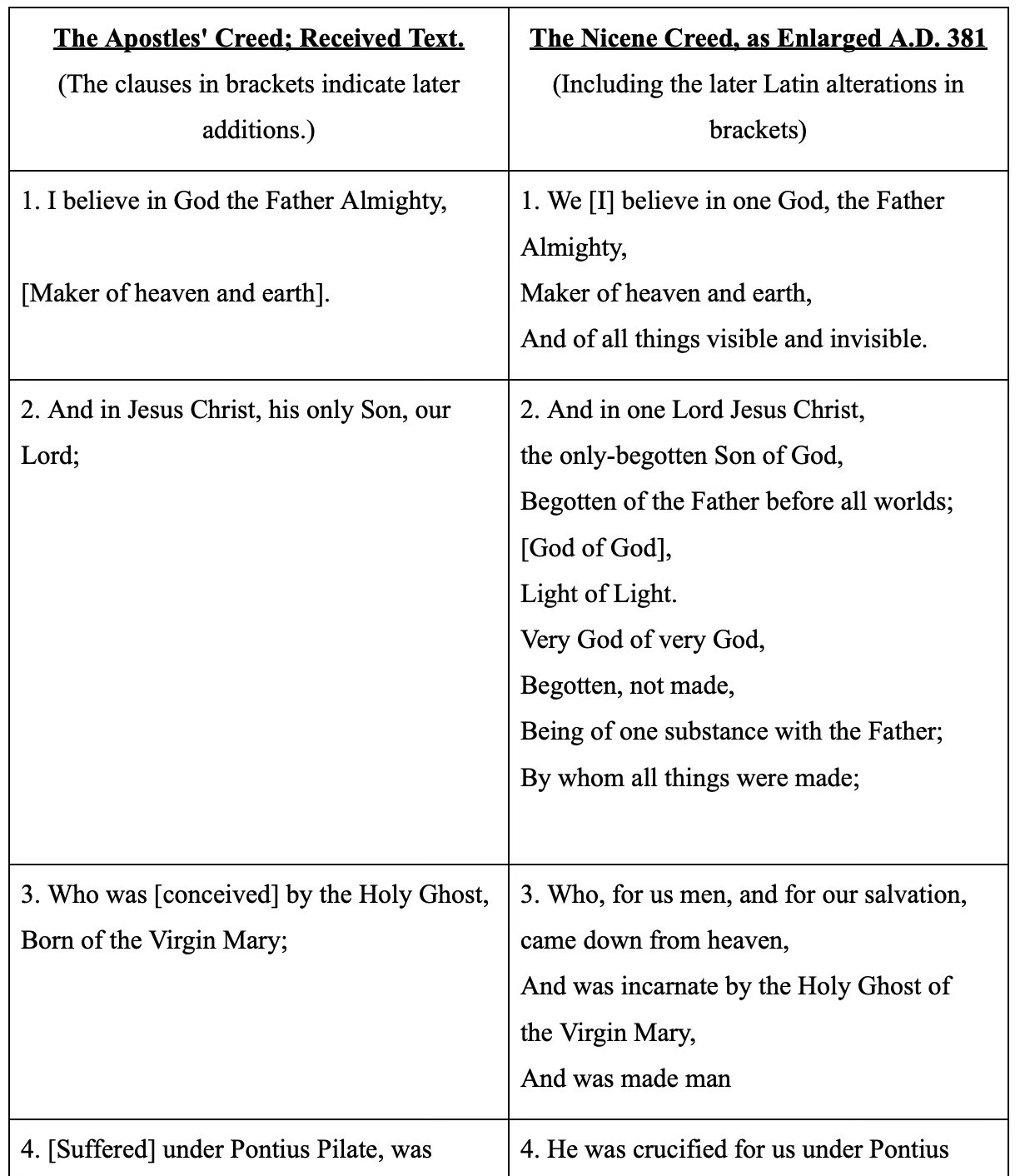

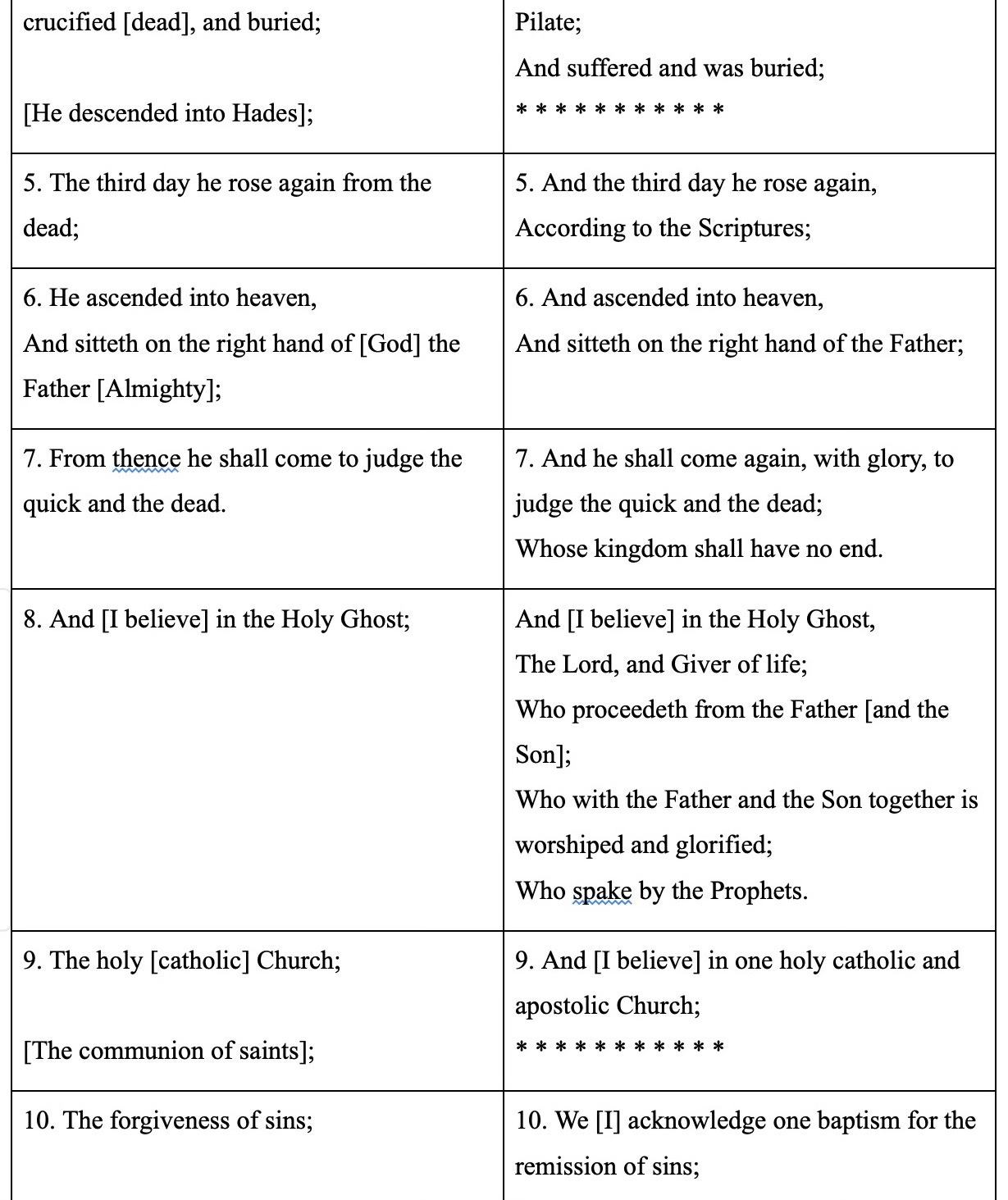

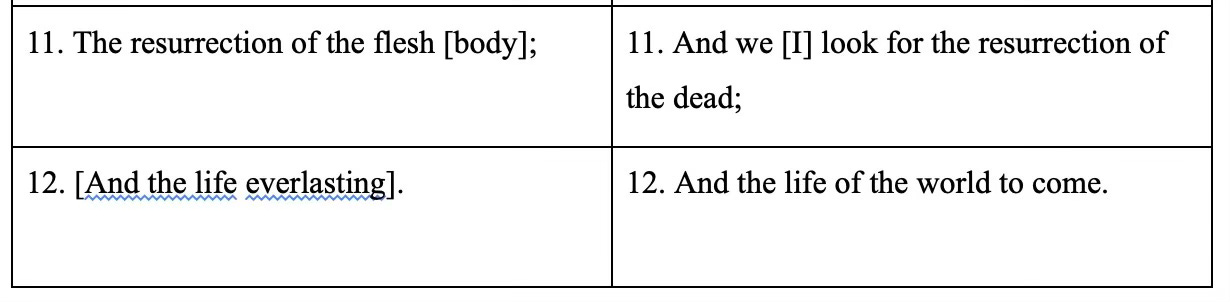

It is instructive to compare The Apostles’ Creed and The Nicene Creed in parallel so one can easily see their agreement, the expansions made in the latter to combat the Arian Heresy, and any place where there are otherwise some differences to note.

Apart from the Filioque clause and its important theological implications we find that the church universal, East and West, all can heartily affirm this creed as well as The Apostles’ Creed. In some ways The Nicene Creed is more helpful because it is more explicit, but it should be noted that, while the distinctions and additions made in The Nicene Creed are incredibly important and appropriate, every time we get more explicit about the specifics of what we believe as Christians the more we divide ourselves from those who cannot affirm our statement of faith. Doctrine necessarily divides. The more general we can be, while still being orthodox, the more inclusive we can be towards other Christians who don’t believe or practice the faith in the exact manner we do. When, however, we draw lines over doctrinal issues we necessarily say “everyone on this side of the line is with us, everyone on that side is against us.” The question is not “should we ever do this,” but “when should we do this” and “to what degree?”

Clearly whether or not Jesus is God is a matter in which it is appropriate not only to draw a line in the sand, but to chisel one in stone. The earliest form of The Nicene Creed appended the following statement after the creed (which is not usually included with the later Nicene-Constantinopolitan of 381).

But those who say: 'There was a time when he was not;' and 'He was not before he was made;' and 'He was made out of nothing,' or 'He is of another substance' or 'essence,' or 'The Son of God is created,' or 'changeable,' or 'alterable'—they are condemned by the holy catholic and apostolic Church.

Undeniably this is strong language, but the deity of Christ is not a small or insignificant matter. It would be easier to condemn such strong language if it were used in regard to where to place the pulpit or what color the church carpet should be or even of the more serious matter concerning the right mode of baptism, but as it is concerning the most central issue there is, the very being of God, it is appropriately strong. The matter of the procession of the Spirit, whether he proceeds from the Father only or from both the Father and the Son, is also very important, but is it as central as the deity of Word (Son) of God? Clearly some Christians in the history of the church thought so.

In the final two lessons after this we will consider the Athanasian Creed and the Definition of Chalcedon. As we do so we will see that these latter ecumenical creeds continued to develop in their clarity and specificity. They did so for good and important reasons, but as they did so they necessarily drew not only a line, but a circle, around those who are to be considered orthodox and divided themselves from those who are heretical (or at least in serious error). Of course, not every important theological disagreement is an issue that should divide Christians from being able to fellowship with one another or from worshipping in the same congregation or from recognizing one another as a brother in Christ. Deciding, however, what is essential to salvation versus what is merely very important to sound doctrine versus what is tertiary and only of minimal importance isn’t always easy. The more specific a creed gets the less ecumenical it can be.

Study Questions

Grammar Questions: (The Information of the Text)

What is the longer name of The Nicene Creed?

In what notable way is The Nicene Creed different from The Apostles’ Creed concerning its development?

What false teaching was Arius of Alexandria spreading about the Word (Son) of God?

Contrary to Arius, what did Alexander teach concerning the Word (Son) of God?

Who ordered a council to be convened to address the Arian heresy and where did they meet?

How many bishops attended the council and how many sided with Alexander on the matter?

According to the reading, why did the “vast majority of the council” affirm the position that was championed by Alexander?

What false teaching did the Second Ecumenical Council address and who convened that council?

What does “Filioque” mean and what did debate over the addition of this clause help to bring about?

What happens “every time we get more explicit about the specifics of what we believe as Christians?”

According to the text, why was the “strong language” about the necessity of believing in “the deity of Christ” appropriate even though it might cause division?

Logic Questions: (Interpreting, Comparing/Contrasting, Reasoning)

Why might it be inevitable that some creeds should have a “reactive” quality as opposed to being purely “proactive?”

Consider the debate over whether the Word (Son) of God is only of a similar substance (ὁμοιούσιος) or of the very same substance (ὁμοoύσιος) as the Father. How important is this debate? Is there really that much difference between the terms “same” and “similar” that it should be such a divisive issue? What other subsequent doctrines of the Chrsitian faith might be impacted by this debate? Explain what you think and why.

What might we infer about Arius from the fact that he refused to recant his position even after the council ruled against him?

What difference do you understand it to make if the Filioque clause is accepted or rejected?

In the second clause of The Nicene Creed it says that the Son is “Begotten, not made.” What does this mean? In what way might he be the former but not the latter?

How is the deity of Christ emphasized in the third clause of The Nicene Creed in comparison to The Apostles’ Creed? What makes the language here stronger and more explicit on this point?

How is the deity of the Holy Spirit emphasized in the eighth clause of The Nicene Creed in comparison to The Apostles’ Creed? What makes the language here stronger and more explicit on this point?

When comparing The Nicene Creed against The Apostles’ Creed you will notice the absence of two statements in the Nicene Creed which are present in the Received Form of The Apostles’ Creed. Which statements are missing? What might account for the reason these statements are in the Received Form of the Apostles’ Creed but not in the Nicene Creed? (Hint: You may want to review Lesson 2)

What did the author of this essay mean by saying “Doctrine necessarily divides?” Why would that be the case?

Rhetoric Questions: (The Analysis of Ideas in the Text)

Define the idea of “unity.” What is necessary in order for a group of people to be in unity with one another? How important is it to have unity? How does the presence or absence of unity within a group affect it? Is there anything which is more important than unity? If some things are more important than unity, what would be a good example? If nothing is more important than unity, why do you think this?

Theological Analysis: (Sola Scriptura)

Read John 1:1-18, Philippians 2:1-11, and Colossians 1:15-20. How do these passages help to affirm the biblical teaching that Jesus (the Son) is truly divine and of the same substance as God the Father?

Read Genesis 1:1-2, Matthew 28:19-20, and Acts 5:1-11. How do these passages help to affirm the biblical teaching of the deity (true godhood) of the Holy Spirit?

Read John 14:25 and John 16:5-11. How might these passages impact the discussion over the Filioque clause?

There is much more to learn about this fascinating time in the church's history. For instance, Athanasius (who had been a deacon under Alexander) fought for years after the council of Nicaea to champion the biblical doctrine even while Arius’ heresy continued to grow. His work, which includes the masterful book known as On The Incarnation, is an incredible example of God’s grace and mercy, as well as the power of faithful preaching and teaching, to correct an erring church.

Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom, pg. 26.

Thank you for putting together this series!