Herodotus of Halicarnassus is often referred to as the “Father of History.” A Greek man, he was born c. 484 B.C. to a fairly well-to-do family and given a liberal education. His own writings make clear that he was well familiar with the great works of literature that preceded his own time. He makes many references to the works of Homer and other poets and dramatists, as well as many philosophers, throughout his Histories. There is evidence to suggest that the great tragedy writer, Sophocles, was a personal friend of Herodotus and also that Thucydides, another famous Greek historian, met him one year at the Olympic Games.

His moniker as the “Father of History” is well deserved because he is one of the earliest authors to record history as a history itself. Prior to Herodotus the historical writings in the Western world were either chronicle, mythical, or incidental.

The chronicler of history would record information about events, people, and places, but these typically only concerned fairly local matters and addressed the then current (or recent) events. Hence we might think of the biblical books named first and second Chronicles wherein the doings of the various kings of Israel and Judah (and God’s interaction with them and his people) were recorded at that time for the sake of later generations. A historiographer (writer of history) is not the same as a chronicler. A historiographer does not merely write down recent events, he looks back into the deeper past and researches what has happened in times gone by. He makes judgments about the quality of sources. He orders the gathered material into a flowing narrative. Generally the historiographer looks at a wider picture of things, geographically and temporally, than does a chronicler.

The mythical writer of history seeks to tell people why things are the way they are now by offering a story about something which occurred in the past. It is very important to understand something which is very often misunderstood in our own day, namely, mythical is not a synonym for “false.” A story which gives an explanation as to the reason why things are as we now know and experience them can be either true or false. A myth is not false by necessity just because many myths happen to be not literally true or historically accurate. It is in light of this that we can say that both the stories concerning the Egyptian God Ra riding the sun as a chariot across the sky and the biblical story of Adam’s sin in the garden of Eden are both mythological. The former tries to make sense out of the observable course of the sun as it goes across the sky each day and the latter seeks to explain why things in this world are broken and need fixing. The former happens to be false, the latter happens to be true, but both are stories trying to explain why things are the way they are now by means of a story from the past, both are myth. Christians heartily affirm the historicity of our first parents, Adam and Eve, but we also should be willing to recognize that this narrative wasn’t written as a history per se. Were it so, we could probably think of a whole lot of other things we would have liked the historian to have included.

The incidental writer of history (and there is not alway a well defined void between this category and that of the former) would include the poets and dramatists who tell us great stories of war, tragedy, love, and all the rest. Homer wrote of a war that took place at a city called Troy, and this seems to have really occurred. Many other details contained in his Iliad may have historical grounding as well, but the historical elements of those stories tend to be more incidental than the main point. The Iliad and Odyssey mention real places and historical events, but their purpose is not trained upon passing on a history book. Stories like these focused upon passing on the paideia of their people, their way of life, training their children to love and seek after the virtues most precious to them. Undoubtedly, the ancient hearers1 of these stories would have absolutely held them to be true, but their idea of the truth in them would have likely been less wrapped up in the notion of whether or not they were historically accurate in the way a modern reader might now demand.

With those three categories in mind, we can now make sense of why people would call Herodotus the “Father of History.” He did not receive that title because all recording of history in any sense of the word began with Herodotus, but because historiography (the writing of history as its own discipline) did. Herodotus set out to write a history book and he did so by gathering sources through his many great travels throughout the world, talking to people and learning the stories they had passed down, reading their books, seeing the physical sites where great battles had been waged, and he began to try to make critical distinctions about how much weight to give to different sources of information. Herodotus, though far from employing modern standards of historical criticism (both for good and ill at times), was among the first to place competing tales of certain past events next to one another and then offer his reasoning for why he thought one should be preferred as more probable than the other. This was a major step forward from what in times past had been a fairly uncritical and open acceptance of the tales passed down.

It was most likely because of Herodotus’ wide ranging travels which put him in a good position to start making some critical distinctions in his histories. In the ancient world, indeed in all but the very modern world, people didn’t usually travel very far from home. The exceptions are notable in history for the fact that they are exceptions to the rule. Most often if people ranged far afield from their home they did so for the sake of war and conquering, or were dislodged due to a famine, etc. That Herodotus set out as a globetrotter simply to learn about other lands and people is fairly unprecedented for his time. His travels allowed him to hear multiple versions of the same stories, myths and narratives retold from different cultural perspectives, tales of battles gone by from the winners, the losers, and third parties, and all of this produced in Herodotus a rare perspective to the fact that people tell the same stories but with different details and outcomes. Those differences would be largely unknown to most people who never went further than a few miles from home, but Herodotus came to see it and it prompted him to reason about how to deal with competing information and to make some judgments.

The World that Herodotus Knew

The historian George Swayne, in his own introduction to Herodotus’ Histories wrote of Herodotus, saying,

His early manhood was spent in extensive travel, in which he accumulated the miscellaneous materials of his narrative. He visited, in the course of them, a great part of the then known world; from Babylon and Susa in the east, to the coast of Italy in the West; and from the mouths of the Dnieper and the Danube in the North, to that cataracts of Upper Egypt southwards. Thus his travels covered a distance of thirty-one degrees of longitude from east to west, and twenty-four of latitude from North to South — an area of something like 1700 miles square.2

No one in his time could more aptly have been called a “man of the world” than Herodotus.

In his composition of his history he covers a great many things. His ultimate goal was to help his readers understand the driving factors which led to the Greco-Persian War. Xerxes I3 led a gigantic army across great distances in an attempt to conquer the Greek people. His army was so large that Herodotus describes several small rivers failing to be able to support them as they sought enough water for the troops, their horses, and their livestock. Herodotus ascribes as many as five million men forming Xerxes’ fighting force. Many of those would have been poorly trained and poorly armed men, but Xerxes sought to crush Greece by sheer force of number.

He would have gotten away with it too if it weren’t for those meddling Spartans. Greece in the ancient world was a collection of city-states and lacked any kind of centralized power. Often those city-states warred upon one another. Despite being fellow country men, the differences between city-states like Athens and Sparta were very real. Herodotus sometimes illustrated this in his history in humorous ways, emphasizing the fighting nature of the Spartans, the eloquence of the Athenians, and their total inability to respect each other. Still, it was necessary to band together or perish when Xerxes came to Greece.

Many famous battles were fought during this war but few as famous as the Battle of Thermopylae (480 B.C.), though the Battle of Salamis and the Battle of Marathon come admittedly close. Greece was unprepared to deal with what was coming their way with Xerxes’ army. They needed time to gather their forces, agree who would lead (not an easy task), and to prepare to make a stand. While much of that was still being hammered out, Persian forces drew ever nearer. It was a group of 300 Spartans, including King Leonidas, who stood in the gap (literally) to hold off the tremendous invading force. Thermopylae, known also as the “hot gates,” formed a relatively narrow pass which the Persians needed to use to enter further into Greece. It was there that the Spartans (and it must be said, a good number of other troops from other city-states) made their stand. Success in this battle was never really hoped for (if by success one means “total victory” over the Xerxes’ army), but success was in fact dramatically achieved if you measure it in the time that these brave men gave to their countrymen to amass a counter army.

Herodotus details the many political factors and intrigues, including the development and change of power in various nations, that created the condition which led to this great war. He further did a masterful job of providing narrative concerning key battles during the war and all of the conditions and personalities that played into the various wins and losses. One would be wrong, however, if they expected The Histories to stay laser focused on these matters at all time. Again, unlike modern historiography, Herodotus felt very free to wonder. He takes long forays and field trips into discussions about local customs, religion, fashion, and food. Very often he makes sure his reader knows how the locals of a given place like to wear their hair! He also tells many amusing stories from all over the world, some historical, some folktales, but all interesting.

He arranged Histories into nine books, each of those named after the nine muses (the goddesses of inspiration). It’s a large book and many modern readers may find it a work of endurance to read from cover to cover, but those who do will surely be glad for the joyous labor. There is pleasure on the other side of a challenge, and there are few pleasures so sweet as those which enliven the intellect and the imagination in the way that taking a trip around the world with Herodotus of Halicarnassus can.

Below you will find links to each section of the study guide for Herodotus’ Histories as they become available. For this study we are making use of the translation by George Rawlinson. If you would like to pick up a copy of the book to join in the study you may do so by clicking HERE. For a list of other Great Books study guides already available, in development, or planned for the future you can click HERE.

Book One: Clio

Book Two: Euterpe

Book Three: Thalia

Book Four: Melpomene

Book Five: Terpsichore

Book Six: Erato

Book Seven: Polymnia

Book Eight: Urania

Book Nine: Calliope

For that is how most ancient stories were received, read or recited aloud by storytellers called Rhapsodes.

Herodotus, Histories (Translated by George Rawlinson with an Introduction by George SW (Digireads.Com, 2016), 5.

Xerxes I is also known as Ahasuerus in the Bible. After the failed invasion of Greece he returned home and sometime later married Esther. The story can be found in the biblical book named after the famous Hebrew Queen of Persia.

Thank you for this offering.

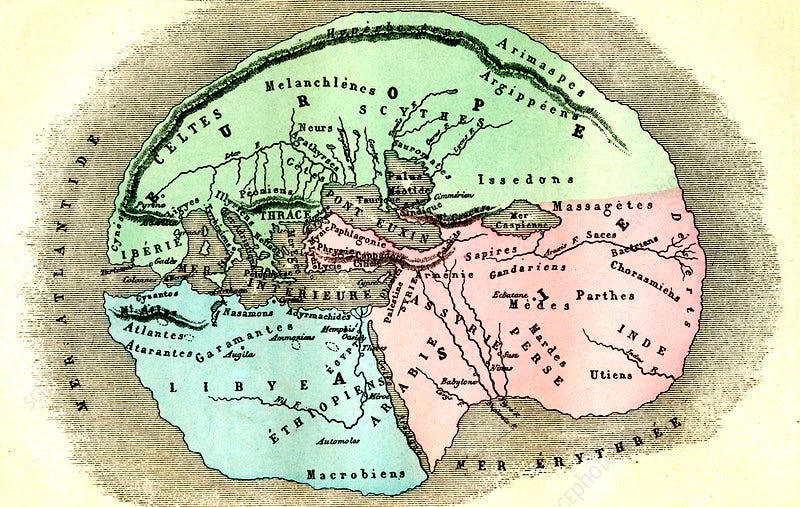

I’ve always like Herodotus and this was a great post making me want to read his histories again. Also, the map of his world looks oddly like the shape of a human brain.